People being told to stay in their homes, numbers of dead being tallied and reported by the authorities, sounding familiar? Theatre and public entertainment such as football being stopped, no this is not London 2020 in the midst of the global Covid 19 pandemic but 1665 when the last major plague outbreak hit London.

There were nearly 40 outbreaks of plague in London between 1348 and 1665 and each of the major outbreaks accounted for around 20% of the population of London, some of the outbreaks would linger on a smaller scale and there were smaller outbreaks that barely seemed worth recording. London has been here before and in times past you could expect a major outbreak every 20-30 years, almost certainly taking someone you knew to the grave if you were a Londoner of those times.

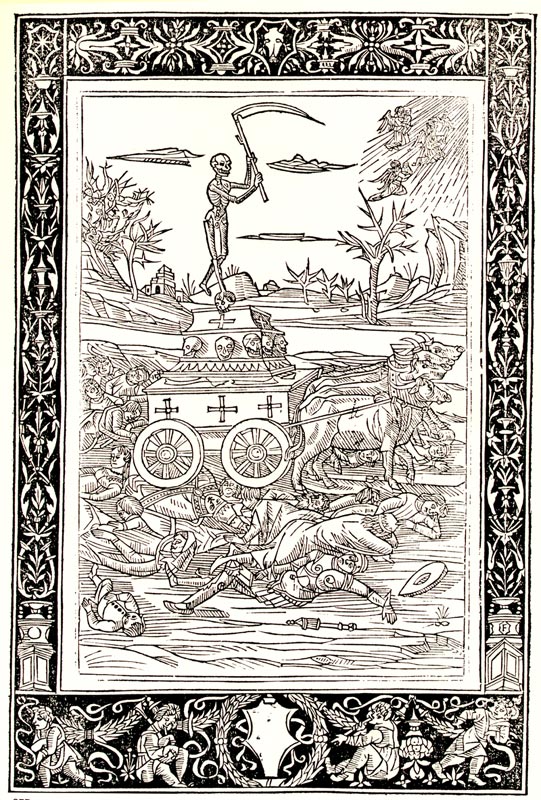

Experts generally belive that these outbreaks were due to bubonic plage, a disease carried by black rats and passed between them by flea bites. If the infected rat dies, the flea and disease needs to find a new host and if that host were human then 60-80% of them could expect to die, often within a week.

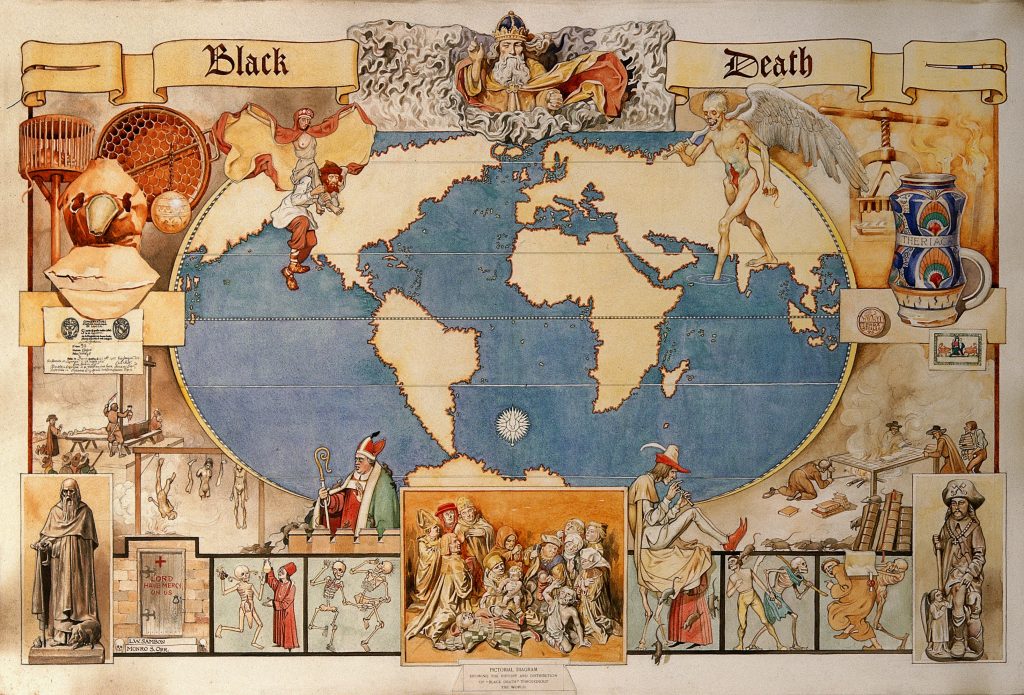

The Black Death

What became known as the black death was the first big outbreak and it hit London in 1348, staying and spreading it’s misery for over two years. The disease had spread from Asia, through North Africa and into Europe, wiping out large swathes of the population as it travelled. When it arrived in London it killed up to 40,000 people, around half the population of the time.

By the 1660’s the population of London had swelled to some 380,000 people, many living in poor and unsanitary conditions. Narrow streets, dirty water and a general lack of hygene or medical knowledge meant the City was ripe for an infection to spread.

In January 1665 a new outbreak of the plague erupted in St Giles-in-the-Field, then a small village on the outskirts of the city.

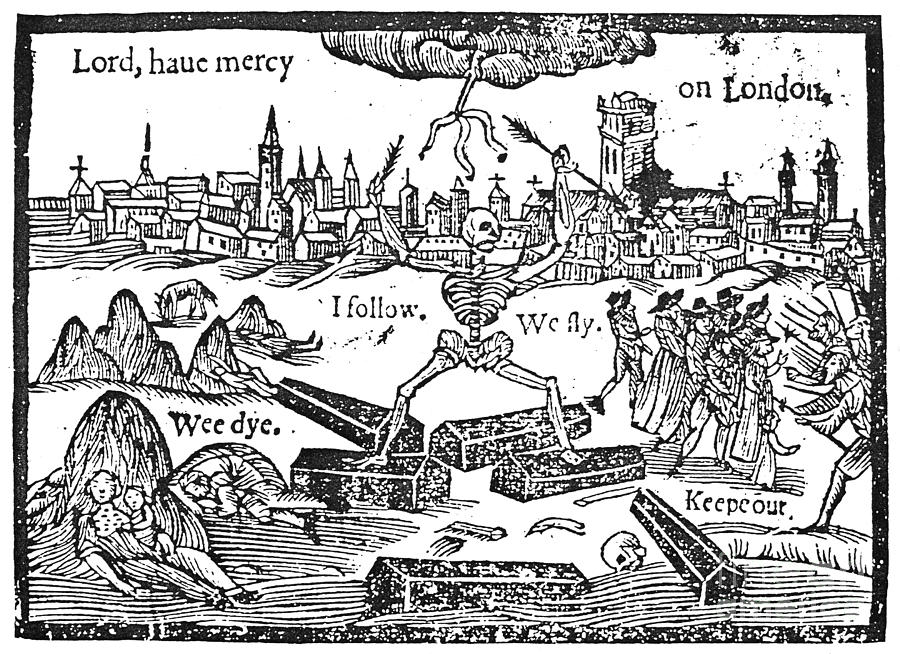

From the 1500’s rules had begun to be put in place to deal with outbreaks, A bale of straw had to be hung outside an infected home for a period of 40 days, people from infected homes had to carry a white stick if they went out to warn others to stay away, dead were only buried at night and the burial accompanied by a bell that was rung for 45 minutes for each burial, infected houses had a red cross painted on the door and the words ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ inscribed. Those inside were expected to remain there for a period of 40 days, assuming they survived that period.

The 1665 outbreak saw over 100,000 Londoners dead within seven months and hygene was getting worse, carcasses and sewage being dumped on the streets or into nearby streams just adding to the problem.

London parishes recorded their weekly dead which were then totted up to produce what was known as the mortality bill, a week in September saw over 7,000 dead before numbers began to fall.

Dr Thomas Gumble, chaplain to the Duke of Albemarle, both of whom had stayed in London for the whole of the epidemic, estimated that the total death count for the country from plague during 1665 and 1666 was about 200,000.

Across London, even today plague burial pits are uncovered where the dead were buried in mass graves due to the sheer volume including over a thousand in the churchyard at St Giles-in-the-Field where it started and more in many other locations. Londoners today could well be walking, working and indeed living over some of these burial pits unkowing of what lies beneath their feet.

In Charterhouse Square, Farringdon a burial pit was uncovered during works for the crossrail line, the Museum Of London came in to study it and it’s believed that up to 50,000 bodies could have been buried here.

It was generally believed that the plague was airborne so many would smoke to try and keep the infection away, many began to smoke for this reason and fires were kept burning in the streets and near homes. Cats and dogs were killed for fear they carried the infection, the same animals that would have helped reduce the rat population and possibly the spread of disease.

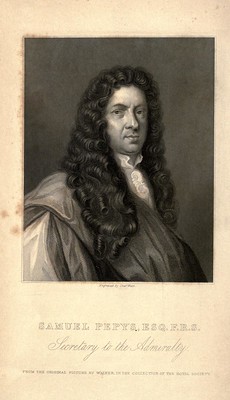

Samuel Pepys the famous diarist lived through the 1665 outbreak and documented many of his experiences, including this passage from the height of the outbreak in August.

“two shops in three, if not more, [are] generally shut up”. Later in the year, on 16 October, he laments the eerie desolation of the city: “But, Lord! How empty the streets are and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets full of sores; and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this dead, and that man sick… And they tell me that, in Westminster, there is never a physician and but one apothecary left, all being dead.”

From it’s September peak the plague slowly receded in London and the city recovered quite quickly. New people moved in to take over the jobs of those that had perished and though the last reported case wasn’t until 1679 life did return to something of a normailty notwithstanding a rather large fire that was about to break out the following year, 1666. The Great Fire of course may well have helped eliminate the plague, killing many of the rats and fleas that were spreading the disease.